- Home

- Tommy Butler

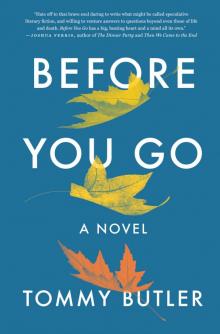

Before You Go

Before You Go Read online

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Part I

Before

Elliot

After

Elliot

In the Future

Elliot

Part II

Before

Elliot

Elliot

After

Elliot

In the Future

Elliot

Part III

Elliot

After

Elliot

Before

Elliot

In the Future

Elliot

Part IV

Elliot

After

Elliot

Before

Elliot

After

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part I

Let them think what they liked, but I didn’t mean to drown myself. I meant to swim till I sank—but that’s not the same thing.

—Joseph Conrad, The Secret Sharer

Before

In a room that is not a room, with walls that are not walls and a window that is not a window, Merriam considers her handiwork. The finished form lies on a table (that is not a table), illuminated by a divine light that Merriam dialed to peak radiance so that she could tend to the last, delicate touches. The brass call it the “vessel,” because it is both the container into which the travelers will pour themselves and the ship that will bear them on their journey. Merriam prefers a different name, one she believes the travelers themselves will use. Humana corpus. The human body.

It’s good, she thinks. Right? Anyone can see that it’s good. Everything the brass asked for and more. The blueprints were detailed, and Merriam followed them precisely, adding her own flourishes where the brass had allowed her some creative leeway. She is particularly fond of the splash of color in the irises, and—for some unknown reason—the spleen. Yes, she decides, it is good.

“Very good,” she says aloud, though her voice is no more than a whisper. The words seem hesitant to emerge, as if the lingering doubt within her were a pair of human hands tugging them back, imploring them to wait until they are sure.

Her internal dialogue is interrupted by Jollis, who appears in the doorway with a hopeful, eager air. He looks around the room, noting the stray bits of cloud in the corners, the row of brightly colored bottles on the shelf. When he sees the body, his typically discriminating aspect slips into one of guileless wonder. “Merriam, wow.” A laugh escapes him. “It’s magnificent.”

“Do you think so?”

“Absolutely.” He moves in for a closer look. “Have the brass seen it?”

“Not the final,” says Merriam. “But naturally they had a hand in it, so to speak. Everyone contributed—the brass most of all.”

Jollis circles the table, continuing his appraisal. “Good bones,” he says. “And I love what you did with the spleen.” Slowly, reverently, he leans in toward the face and gently pushes back the eyelids. He gasps. The eyes glisten, collecting the room’s divine light and amplifying it, before sending it back in a chromatic gleam. “Exquisite,” says Jollis. “They’re going to love it, Merry.”

“Really?”

“Oh, definitely. We’re talking major promotion.”

Merriam tries to hide her excitement. “This is just the prototype, of course.”

“Oh?”

“I mean, it’s finished, and fundamentally they’ll all be the same, but there will be all kinds of variations—different shapes, colors, idiosyncrasies—because obviously the travelers will want that. It’s not like they’d ever declare just one type to be beautiful and then desperately try to imitate it.”

“No, of course not,” agrees Jollis. “That would be ridiculous.” He moves toward the window. “Do you want to see where they’re going?”

Merriam freezes, her insides suddenly aflutter. She does want to see, doesn’t she? The others have been working so hard, and with such secrecy. Finally she nods, and Jollis pulls back the curtain. “Merriam,” he says, “allow me to present . . . Earth.”

There in the window is a shining, distant orb so lovely it is almost painful to behold. Crimson fires warm it from within, while a yellow sun bathes it in light. Argent clouds swirl over an intricate mosaic of tawny sands and emerald wilds. And everywhere the sparkling blue of water—gathered in vast oceans, rushing madly in rivers, falling from an ethereal sky.

Though she should be elated, Merriam feels oddly cold, almost numb. She can’t seem to find her voice, but Jollis’s expectant gaze is on her. “It’s magical,” she says.

“Pretty sweet, right? They say it can accommodate up to two billion people. Any more than that would be a disaster.”

“So, it’s ready to go?”

Jollis nods happily. “Just waiting on the vessel.”

The vessel. Merriam turns back to look at the body on the table. The lingering doubt within her finally crystallizes into a clear danger, a peril against which she might still be able to offer some defense. She begins to shoo Jollis out of the room. “Right,” she says. “The vessel. Almost there! Just one last thing.”

“But you said it was done.”

“Just about,” she says. “You can’t rush these things, after all.” Once Jollis has been successfully ushered out, Merriam returns to the body. She takes one last look at the wondrous new world shining in the window. Then she gets to work.

By the time Jollis returns, Merriam is slumped beside the table, exhausted. She rises to greet him. He gives her a nervous nod and turns his attention to the body, immediately discerning her latest and final edit—a small cavity inside the chest, shaped vaguely like a crescent, nestled beside the heart.

Jollis pales. When he finally speaks, his voice is brittle. “There’s a hole in it.”

“No,” says Merriam. “It’s—”

“What did you take out?”

“Nothing.”

“But what’s supposed to go there?” Jollis gestures urgently. “What’s missing?”

“Nothing’s missing,” says Merriam. “It’s complete.”

Jollis gapes at her as if she just proclaimed she was a jelly bean. “But there’s a hole in it!”

“It’s not a hole,” she insists. Jollis’s distress jangles her nerves, threatening her newfound certainty. “It’s . . . an empty space.”

He doesn’t seem to hear her. “You need to fix it,” he says. “Change it back.”

“It’s too late,” says Merriam. “Look.” She points to the eyes of the body. Though they remain closed, the skin of the eyelids undulates as the eyes dart and roll beneath the surface.

“What’s it doing?” asks Jollis.

“Dreaming,” she says. “First comes the dreaming, then everything else.”

Jollis begins to shake until Merriam fears he will shatter. Instead he begins to move around the room, searching. “Okay, don’t panic,” he says. “We’ll just fill the hole before it wakes up.” He gathers up fragments of cloud from the corners of the room and packs them together, then stuffs them into the crescent-shaped cavity, careful not to disturb the adjacent heart. He draws back and watches as the white mist expands to fill the space. But clouds are restless things, and this one dissipates, dissolving like fog in the morning sun, leaving the emptiness behind.

Jollis grimaces. He begins to gather the divine light of the room itself, sweeping it up in great heaps until his visage is ablaze and the corners of the room retract into shadow. He squeezes the light down, pressing it into the cavity. Illuminated now from both within and without, the crescent space is striking in its beauty. Yet, light being what it is, it cannot fill the void.

“No,”

moans Jollis. He turns to the shelf full of colored bottles. “What are these?”

“Emotions,” says Merriam. “The full spectrum, but I’ve already included the prescribed amounts.”

Jollis grabs a bright red bottle and tilts it over the body’s chest. A shimmering substance pours forth, filling the cavity. Jollis sighs with relief and puts the empty bottle back on the shelf. “There,” he says. “That’ll do it. Which emotion is that?”

“Love.”

“Perfect,” says Jollis. “That should work out just—” As he speaks, the shimmering substance drains from the cavity, leaving it empty again. “What happened?”

“It got absorbed,” says Merriam. “By the heart.”

“Dammit!” Jollis grabs more bottles from the shelf. He pours them in one after another. Each time, the emotion is absorbed by the heart. As Jollis gets to the darker ones, Merriam tries to stop him, but he surges on, frantically emptying bottles until only one is left—a small, twisted vial the color of ash and flame. He begins to pour it, too, into the cavity, but Merriam pushes him away before he can finish.

“Jollis, that’s enough. It won’t work.”

Jollis drops the vial. He slumps, his countenance dimming. “We’re doomed.”

“But why?” asks Merriam. She is scared now. She has never seen him so distraught.

“Because it’s got a hole in it!” he cries. “And they’ll know it, Merry. They’ll feel it, and they’re going to constantly be looking for things to fill it with. They’ll eat too much. They’ll fall in love with the wrong people. They’ll hoard money, and watch too much television, and buy useless crap from holiday catalogs, like potato scrubbing gloves or a spoonula.”

“What’s a spoonula?”

“Never mind.” Jollis softens. He is more despondent than angry. “Don’t you see? Nothing will work. There will always be this void. No matter how they try to fill it, they will always want the one thing we can never give them enough of.”

“What’s that?” asks Merriam.

“More.”

Merriam feels hot tears gathering inside her, wanting out. She realizes she hadn’t thought it through. Not completely. “I didn’t mean for that to happen,” she says quietly.

Jollis sighs. “But why did you do it?”

Merriam glances out the window. “Because of that world,” she says. “I saw that beautiful world we made for them, and I was afraid they’d love it so much they’d never want to leave. So I gave them a little empty space, to make sure they’d come home.”

Elliot

(1981)

The leaves fall in a mad rush—an unruly circus of yellow, orange, and red—hurled down from the trees by a mutinous wind. It’s easy to get lost in it. I stand at the center of our little front yard, staring up at the long-limbed giants and the roiling cauldron of sky. My eyes fill with color, my ears with the sweep of air through the branches. The sharp scent of ozone heralds distant lightning. Nothing else exists, and a long moment passes before I remember who I am or what I’m doing out here beneath the front edge of an autumn storm. I am Elliot Chance. I am nine years old. I am catching leaves with my brother.

Action gets the glory, but most great endeavors begin in stillness. Leaf-catching is no exception. After the opening of the front screen door and the rush to the middle of the lawn, your first move is not to move. You stand frozen, gauging the speed and direction of the wind, feeling instinctively for any pattern in the bend and sway of the trees. Once all the data is collected, once it has run through you and blended with whatever else is inside you until the distinction between you and the storm begins to blur—and providing you do not forget yourself in the process—you do what every good adventurer does at the outset of a good adventure. You follow your gut. In this case, you pick that particular spot in the yard where you believe the leaves are most likely to fall. Once there, you bend your knees, keep your hands up, and wait.

Falling leaves do not, of course, drop in straight and steady lines. They are unpredictable, feisty, weird. They hitch and pause their descent at random, which makes them difficult to catch, but which also provides the best opportunity for catching them, because among those sharp turns and changes of speed and other machinations there is often a midair hesitation, a momentary hovering, when the little scrap of color checks its fall but doesn’t immediately replace it with anything. For a split second, it simply stops, and—if you’re close enough—a split second is all you need. Your knees uncoil. Your hand fires out. Your fingers widen to cast the largest possible net, and—

“Ha!” yells my brother, knocking down my outstretched arm with an impish glee. The leaf slips to the ground, uncaught. My brother laughs and rushes past me. “That’s a miss!” he shouts. “Doesn’t count.”

Dean is just two years older than me, yet it would be hard to imagine two more disparate styles of leaf-catching. We begin in the same way—two slight boys with hazel eyes, rushing out the front door, looking very much alike except for his light, sandy hair contrasted with my dark brown. Yet Dean doesn’t stop rushing. He is all bustle and bluster, jumping at leaves one after another like a young golden retriever dropped unexpectedly into a frenzy of skittish waterfowl. His misses far outnumber his makes, but this doesn’t seem to faze him. He moves so quickly from one attempt to the next that I would question whether he is even aware of the results, but for the fact that he proclaims his total catches after each successful one.

“Seven!” he calls, crumpling a yellow oak leaf in his fist. For Dean, leaf-catching is neither meditation nor exultation. It is a competition, pure and simple—one in which disrupting your opponent is perfectly fair, and loudly tallying your points is good strategy. “How many do you have?” he asks, while simultaneously diving for a catch, a feat that, I admit, is pretty impressive.

“Five,” I tell him.

I’m lying. I don’t know exactly how many leaves have been diverted from their paths and into my pockets, but it’s at least fifteen. Don’t get me wrong. I like winning. Winning feels better than losing, but both are necessary ingredients of the playing itself—if the playing is a competition, which it is to Dean. The truth is that my brother likes winning much more than I do, and I like playing with my brother. I enjoy watching him tumble around the yard like a happy clown.

“Nine!” he shouts.

The game continues until a flash of sheet lightning kindles the horizon. We stop and count the passing seconds. Five, before the sound of thunder reaches us, which we know means the heart of the storm is five miles away. The sky darkens, and what light remains grows softer and sharper. The world around us appears etched in bronze, yet it moves and breathes. Unnaturally so, it suddenly seems to me. The clouds gather so quickly they appear to have a purpose. The trees nod and tilt emphatically, full of urgent whispers, until I am certain they are aware of us.

“Dean, look!” I say, laughing. “The trees are alive. They’re trying to grab us!”

“Weirdo,” he says, not pausing to look. “They’re not alive.”

I am about to argue when the first raindrop strikes my head with a firm plunk. More follow—big, fat beads that multiply as the sky opens up. We are soaked within seconds. Dean is already running for cover.

“Game over,” he calls. “I win. No more catches. They won’t count.”

But I am done with leaf-catching now. I lie down on the grass, face upward, and open my mouth as wide as I can. Gathering raindrops is a decidedly passive pursuit.

“Dean, c’mon,” I say. “Catch the drops in your mouth.”

“I already caught like a billion,” he says.

He heads for the house. The rain falls in a mass, with a clamor like the sound of a restless crowd, so that I barely hear the screen door slam behind him. My mouth fills with raindrops, and I laugh when I realize I am essentially drinking the sky. The storm intensifies. Lightning splits the air, followed instantly by a deafening crack of thunder that shakes the earth under my back. Only the wind has lessened, as i

f to make room for the deluge. All the leaves but one hold fast to their branches. This last one, a defiant red, weaves and twirls toward me like an aerialist struggling to remain graceful through the bombardment of water.

“Elliot,” calls my mother. She is standing behind the screen door, next to my brother. I can just make out the puff of her hair, surrounding her head like a little cloud. Her voice is an urgent mixture of anger, love, and fear. “Come inside, please.”

The thunder rolls again, and again the earth rumbles in response. I feel it along my spine like the heartbeat of the world. The lone leaf pushes on through the storm, bravely persevering through the last of its acrobatics until it is just above me. Once there, it takes a final bow, turns a shapely pirouette, and lands softly at the center of my chest.

“Now, Elliot,” my mother calls again.

That night I see the first of the monsters. The rain has passed, my parents and Dean are asleep, and the world is silent. I lie awake in bed, staring at the closed door of my room. I’m thinking of the thunder and the awakening of the trees, and how the storm has left my senses heightened, so that as I gaze at the brass knob of the door I can see—even in the near darkness—that it is turning. Slowly and smoothly it rotates back and forth, as if whoever is trying to enter isn’t entirely sure how to use it. I suspect Dean—then recall that, though he may not be much smarter than a doorknob, he does in fact know how to operate one.

There is a click, and the door slowly swings open. Its bottom edge drags over the shag carpeting with a quiet rustle. The hallway beyond is empty. No Dean. No anyone, or so it appears at first. But then I notice a patch of darkness that is deeper than the surrounding night. Its edges are fuzzy and fluid, but it is roughly the size and shape of a person, like a shadow without an attendant body. It glides into my room and stops. Though it has no discernable features, I can tell that it’s smiling at me.

I immediately think of it as a monster, not knowing what else to call this faceless incarnation of night. Yet the label doesn’t really fit. For one thing, I’m not afraid, not even a little. More importantly, the shade just isn’t monstrous. In fact, it proves perfectly friendly, even polite. After a respectful pause, it bows deeply from the waist, one dark arm at its back and the other unspooling before it in a way I’ve only seen in movies. Maybe it’s British, I think.

Before You Go

Before You Go